The NKG Reader

Edition #2

Mad Man’s Daughter

Mad Man's Daughter is a short video compilation of the works of Black African artists and creators and makers of the Black African diaspora. We researched and platformed this collection over UK Black History Month in October 2020. The Mad Man's Laughter is a piece by Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou, she is an Ethiopian nun, pianist and composer, born in 1923 she's seen her country through many a revolution; she is still alive and playing today.

Artists included: Deborah Roberts, Dotun Abeshinbioke, W.E.B. Du Bois, Yinka Shonibare, Kvvαdwo Οβeng, Kara Walker, Tschabalala Self, Shawanda Corbett, Alisha B Wormsley, Ruth Ossai, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Buddy Esquire, Phase 2 and Faith Ringgold.

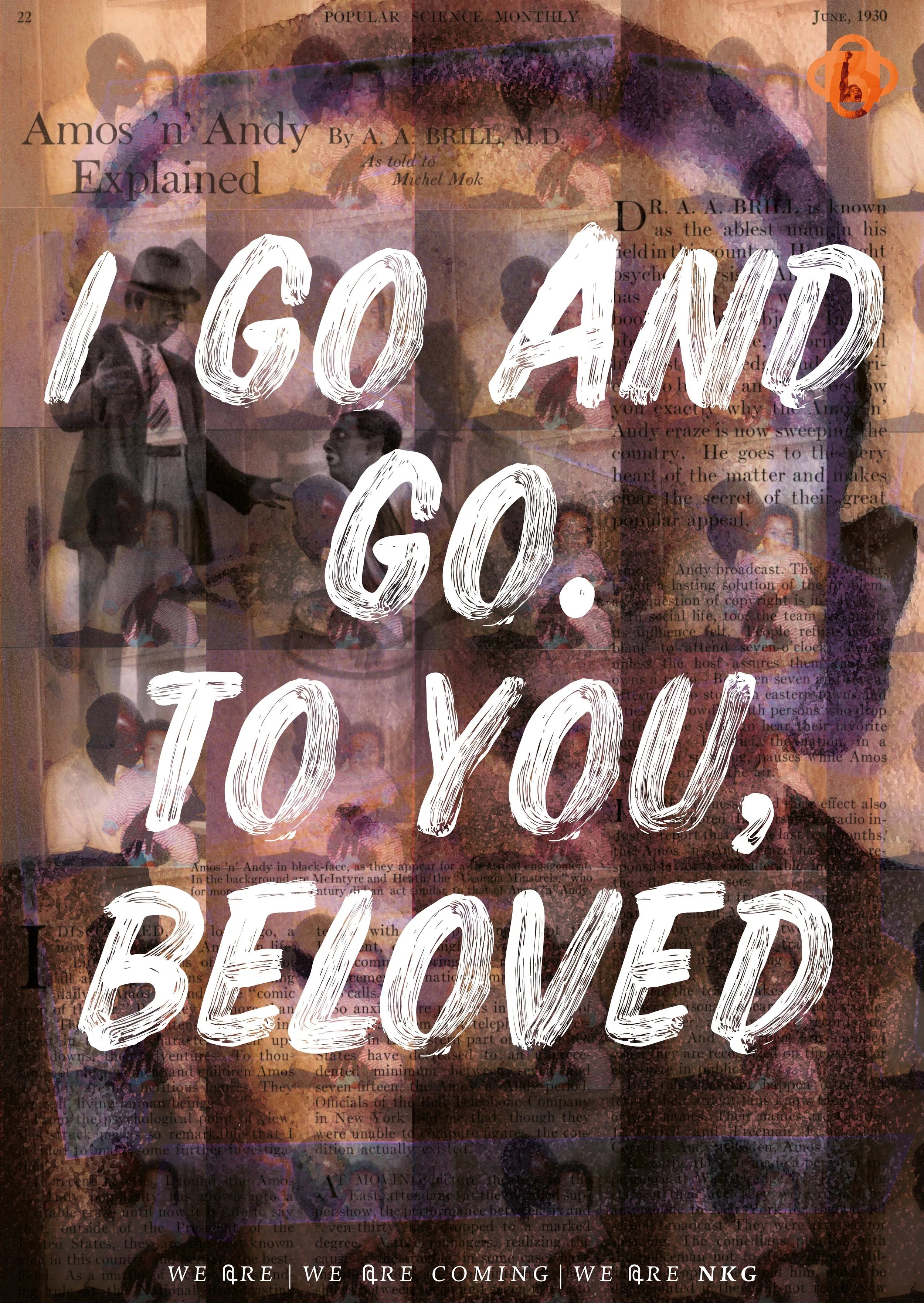

These posters were created in our design studio, Coretta Design. To purchase one of these prints please donate to the NKG Reader and contact us at nkg@nyarkodero.com.

At the end of summer last year (2020) there was a silent collapse and a collective sense of depletion followed. Whilst the protestors in the US marched forward, albeit with less coverage and less noise, the UK started to curl in on itself, like browning autumn leaves the pending threat of new lockdowns and winter exhausted us. We wanted to give something to these physical spaces, a reminder that we all needed to find ways reinvigorate ourselves; that somehow we needed to find a way to keep on fighting, and to reach the end of the next week, month, or year with enough strength to fight some more. For justice. These posters are a call to emotional arms, to unity, and to a growing community of people who are more deliberate in their political activity, everyday.

These prints existed first to be seen in physical form, emulating all we feel about the road that lies ahead, we hope they beckon you to walk with us, physically or otherwise.

Meditating on Double Consciousness

By Rebecca Achieng Ajulu-Bushell

Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake, On Blackness and Being, offers the hold, a space of care that allows us to subvert the violence of racial terror and hold on, to keep on living. Sharpe goes on to describe a state of being within which Black academics are required to use methods and models of research that feed into the service of larger destructive forces in order to create and produce legible works that adhere with academy standards. She explains that by doing this we are “doing violence to our own capacities to read, think, and imagine otherwise. Despite knowing otherwise, we are often disciplined into thinking through and along lines that reinscribe our own annihilation…” Through this race trend whereby everyone ‘wants in’ (to get something out) we have to interrogate our position to, and our grip on, this hold; how do we hold in tension the reality of having to engage with conversations that can feel violent or debasing to the notion of your ‘African-ness’; and thus, your Black skin. This meditation, therefore, seeks to briefly consider the position of Black creators relative to the often times violent modalities of producing ‘legitimate’ work. In identifying the sites within these spaces that require the need for strategic approaches, we also find views critical these strategies; this is an equally important facet of this conversation.

There is a necessity to engage with the modalities of Black creation that are created in spaces occupied with tenants that seek neither to include nor celebrate you. Professionally, this is an acceptable compromise, much like the enjoyment of good food with the knowledge that you will have to wash the dishes. But intellectually, its cumulative effects can feel like an assault. But this is a natural tension of a space that is both a profession and a politics. By politics here I mean the kind of politics that exists in all subversions, to be Black, African and taking up space in traditionally white institutions and professions has a politics about it. We must therefore engage in what Biko calls double consciousness. He writes that double consciousness is knowing the particularity of the white world in the face of its enforced claim to universality; and that the history offered up to Black people is a falsehood that we are forced, in many ways, to treat as truth. This double consciousness there is “knowing a lie while living its contradictions”.

In order to sustain this state of double consciousness I offer up the remedy, or strategy, of safeguarding time for active Black connectivity, or what Sharpe terms Wake Work. This can take many forms of course but inherently it is concerned with methods of encountering a past that is not past. This means to acknowledge the ways in which our heritage of violence permeates our present both intellectually and spiritually. We find example of this kind of violence in the ‘raid’ that Curtain describes in Ghettoising African History. That in the field of African Cultural Studies, traditionally white institutions would seek to raid African universities to further their diversity agendas. These contemporary realities are in some ways violent yet, they exist to further a profession that we must believe can, at some point in its future, subvert its past. My Wake Work is reading Black fiction. A literary product that feels less constrained than its academic counterpart and offers necessary respite to the effort employed to sustain our state of double consciousness. If we are able to linger in the truth of the lies, as we do when Black fiction offers us a way of reading violence that we don’t have to do anything with, only accept; we may be better equipped to lead these spaces to a future whose modalities are less fraught.

Edition #1

Still No Justice & No Peace

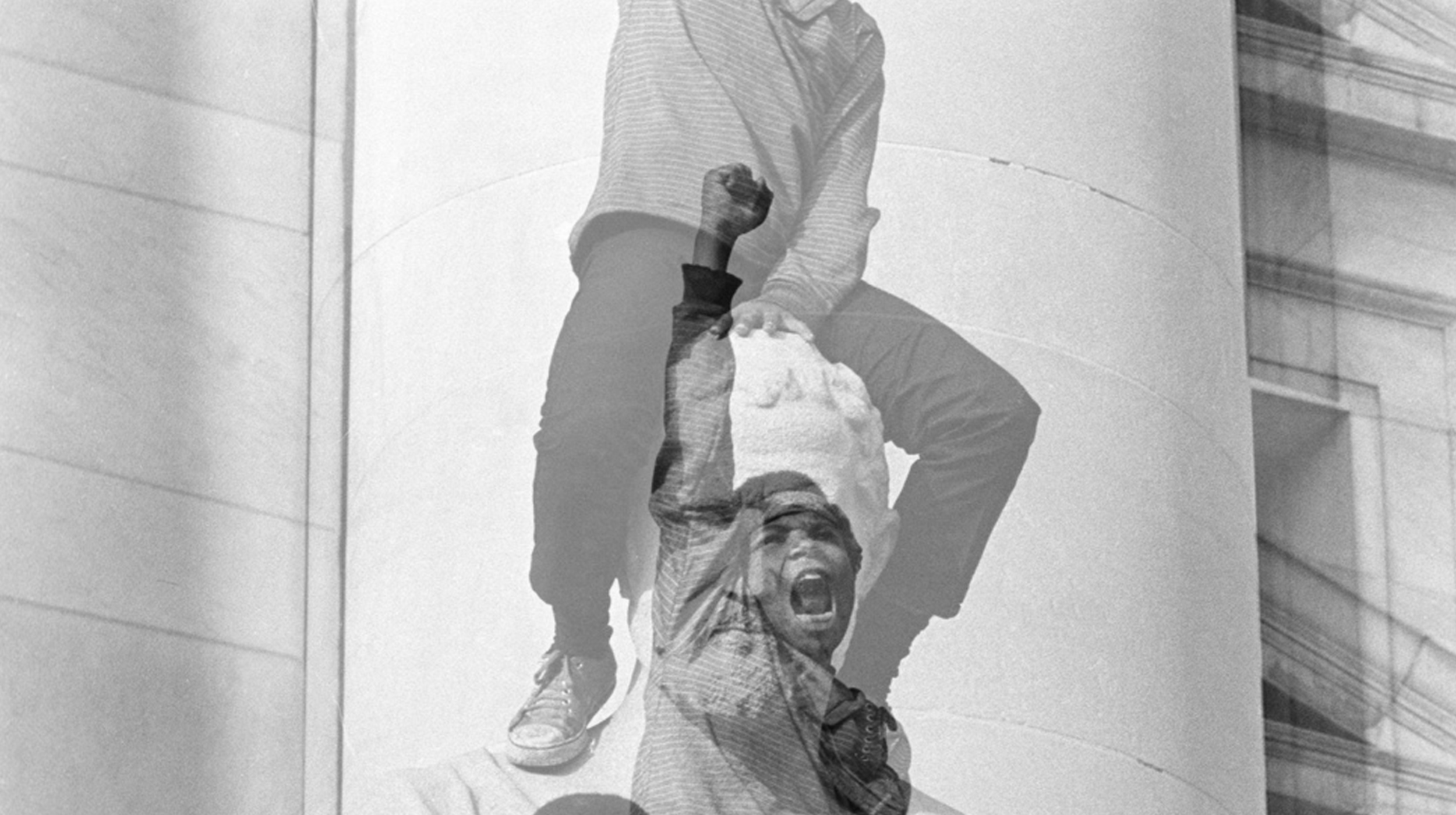

This is a re-run of a piece from our archive. No Justice No Peace, 2015 is an ode to Michael Brown and Tamir Rice. It seeks to pull at the paradox of America’s fear, desire, hatred, and love, of blackness and black culture; told through the lens of reactions to—and footage from—the first wave of the Black Lives Matter movement.

We platform this piece once more to honour those living this same injustice; five years on from the date this short film first screened we are in a different place but it is no better.

The American Council on Education wrote to the Secretary of State and the Acting Secretary of Homeland Security in mid-march, asking questions like ‘if schools close how will international students maintain their visa status?’ and my personal favourite, ‘how will states process visas if US consular offices are closed for an extended period?’ An article on the letter, published on 20th March, for Inside Higher Ed ends like this: “the Department of State referred a request for comment to the Department of Homeland Security. Which did not respond to several enquiries.”

After reading this and similar pieces over the months that followed, I want to go home. I also want not to talk about what’s for dinner or think about the fact that my car back in England has a tax fine and the number I need to rescind that is in a box in a flat in London, somewhere. I feel uncomfortable all the time. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes that the only reason you’d say race was not the issue is because you wish it wasn’t. To be affluent, liberal and Non-American Black is to assume a role of casual indifference to the colour of your skin, to grow up in a white world and hold your difference at the table as everyone else holds their dinner party anecdotes. Then, to admit that you are not stronger than the everyday racism is to confess; to say you are no longer in a state of indifference about your state of difference but rather in a state of fear.

It’s not in my nature to want to go home. My family is between the UK, Kenya, and South Africa, so, like many international students and third culture kids like me—along with many others in this situation—I’m having to drastically reframe what home means. But I miss my community, and to me that isn’t any one place; it’s just not here. Seeking Americana[h]. In a 1979 essay entitled ‘Here’s Ronnie: On the road with Reagan,’ Martin Amis writes “[he] doesn’t care whether people like us. He just wants people to respect us!” It’s this mantra that’s been parlayed into the fabric of the US immigration system, so completely is it designed to put out your fire, to make you feel less than, to demand subservience, and to lead you down the dark road of thinking about all those for whom it won’t work out. It probably will work out for me.

When you finally get to the official websites the font is so small it’s hard to get past the first paragraph. Even before that, you are inundated by the corollary of the American free market, the top searches that come up when you’re trying to figure out an unnavigable mess. The suggested search results are all heavy on the detail you need and reassuringly written; providing just enough information for you to be sure the person who wrote it really knows what’s going on, until you reach the bottom of the page and realise you’re on an immigration law firm’s website. ‘For more, please call us today to find out exactly when and how we can take your money’—immediately and lots of it.

The academic faculty world of Madison is a melding of pseudo-intellectual farm-to-table culture and a community spirit people talk about that doesn’t exist. I planned to be here for two weeks; that was two months ago. And now, with two cancelled flights under my belt, I’m really trying to get home. Home to a place that I have never had any true patriotic feelings for, despite feeling very British here. Home to a place where I rather unwillingly pay my national insurance contribution, because home is a place I have never really thought of as offering me any real protection. And why should I - the UK does bigotry like America does racism—I thought. If you’re someone who has been fortunate enough to grow up without fear, then you did not grow up Black in America. I didn’t grow up Black in America, but I am f[h]e[re]ar now.

In September this year I am supposed to join the African Cultural Studies department of UW-Madison. Along with other international students, I don’t know if I will be here to start my degree. As of 27th May, I have received only two emails from my prospective schools International Student Services department. The first starts with an apology and the second ends with one; there is no information in between that I didn’t already know. Our student visas, as it stands, are conditional upon classes being held in person; if the course goes online we won’t be granted our I-20s and I will be six hours ahead of the last two months’ worth of herbs I’ve planted. A part of me hopes I have no choice but to stay away.

The reality of being a foreign national in America is slowly revealing itself to me; that I should feel like a second-class citizen whilst I fight for the pleasure to stay in a country that would have me remain a second-class citizen. Madison is a liberal enclave in the heart of the Midwest, the blue reason Wisconsin runs purple, a college town of extortionately priced organic produce and self-serve grains (people spend hours spooning them into little glass jars they’ve brought from home, and smile while they pay $206 for 12 items; I do wonder how they think all this stuff got to be in their local co-operative: in plastic). This is a bubble of white do-gooders who have signs in their kooky front gardens (read: yards) that say ‘black lives matter here’ and ‘this is your home’; and through all my time here when I see those signs I still think, if this is my home too, why is the door—why are all the doors—so firmly closed.

So, it goes like this; maybe I spend five years here getting my PhD, and sometime within that period I become inured to my fear, or it becomes part of my existing relationship with cortisol that’s killing me faster than it should. So much is now written on how nothing but a Black person’s experience of racism is eroding them on a cellular level. Many BLM marches and ‘I Can’t Breathe’ protests later. So, now I have a green card (maybe) and I’m still scared, scared to be on my own, scared to forget that I need to remember—always—I’m Black here. That the way people look at me is probably about that, that the fear I feel when we cross the city limits and drive through Beloit toward Chicago is the fear that if I see someone get stopped and he’s Black, I’m his witness. This place [Madison] isn’t big enough to protect my psyche from the daily rub of America’s scarcity narrative: ‘there’s not enough for everyone so I must eat first’ and ‘I would rather she didn’t eat if I can’t eat’—instead of letting the state feed you both—I mean, in theory. This seems to be the crux of it, that American racism is the technology designed to keep the scarcity narrative running smoothly, a swelling mania that’s fuelled everything from the buying of people to the buying of a wall. And as a light skinned mixed-race woman with a British Passport, an Oxford education and a direct line to the [white] liberal elite, how do I talk about George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, when we are not them, but they are us. Trump’s or Obama’s, I just wish it wasn’t America.

It’s Not Us

Audio recordings from the murder of George Floyd, a statement made by police in the manhunt for white murder suspect Peter Manfredonia, and an interview with a protester in Minneapolis. It’s not us.

“It’s not us. And no it’s not gonna end today, I can’t tell you it’s gonna end tomorrow, I don’t know when it’s gonna end, but it’s for ya’ll to start. We not the ones that’s killing us. Ya’ll killing us.

We can’t make a change, if ya’ll don’t change.”

In memory of George Floyd 1974-2020. Rest in Power.